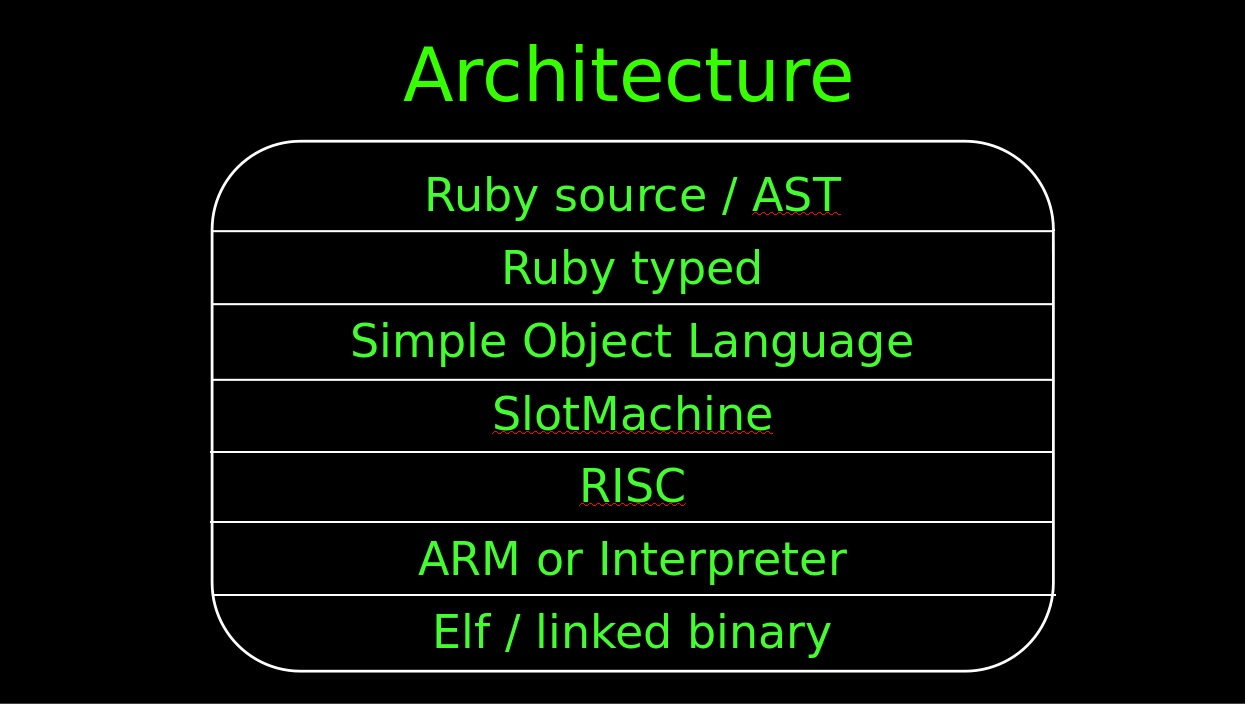

RubyX architectural layers

To implement an object system to execute object oriented languages takes a large system. The parts or abstraction layers are detailed below.

It is important to understand the approach first though, as it differs from the normal interpretation. The idea is to compile ruby. The argument is often made that typed languages are faster, but i don’t believe in that. I think dynamic languages just push more functionality into the “virtual machine” and it is in fact only the compilation to binaries that gives static languages their speed. This is the reason to compile ruby.

Ast + Ruby

To compile and run ruby, we first need to parse ruby. While parsing ruby is quite a difficult task, it has already been implemented in pure ruby here. The output of the parser is an ast, which holds information about the code in instances of a single Node class. Nodes have a type attribute (which you sometimes see in s-expressions) and a list of children.

The first layer in RubyX is the Ruby Layer that basically models the ast in a concrete syntax tree. This means there is one class per node type.

The Ruby layer is then used to transform the data into the Sol layer. Eg: Implicit block passing is made explicit, conditions are simplified, arguments are simplified, and syntactic sugar is removed.

Simple Object Language

Simpe, in this context, means that it is much simpler than ruby.

The main purpose is to simplify existing oo languages down to it’s core components: mostly calling, assignment, continuations and exceptions. Typed classes for each language construct exist and are responsible to transform a statement into SlotMachine level below.

Examples for things that exist in ruby but are broken down in Sol are unless , ternary operator , do while or for loops and other similar syntactic sugar.

SlotMachine

We compile Sol statements into SlotMachine instructions. SlotMachine is a machine, which means it has instructions. But unlike a cpu (or the risc layer below) it does not have memory, only objects. It also has no registers, and together these two things mean that all information is stored in objects. Also the calling convention is object based and uses Frame and Message instances to save state.

Objects are typed, and are in fact the same objects the language operates on. Just the functionality is expressed through instructions. While source methods are defined on classes as Sol, when they are compiled to binary, they are made type specific. These CallableMethods hold the binary and are stored in the Type.

The SlotMachine level exists to make the transition to Risc easier. It has a very abstract, high level instruction set, where each single instruction may resolve to many (even tens of) lower level instructions. But it breaks down Sol's tree into an instruction list, which is conceptually a much easier input for the next layer.

SlotMachine uses a class hierachy to represent instructions, and this fact may be used to extend the systm functionality. This feature is used in the Builtin layer of functions. These functions are coded at the SlotMachine level, as they can not be expressed in ruby. Examples include instance variable access, integer ops...

Risc

The Register machine layer is a relatively close abstraction of risc hardware, but without the quirks that for example arm has. The Risc machine has registers, indexed addressing, operators, branches and everything needed to implement SlotMachine. It does not try to abstract every possible machine feature (like llvm), but rather “objectifies” the general risc view to provide what is needed for the Slot layer, the next layer up (and actually Builtin functions).

The machine has it’s own (abstract) instruction set, and the mapping to arm is quite straightforward. Since the instruction set is implemented as derived classes, additional instructions may be defined and used later, as long as translation is provided for them too. In other words the instruction set is extensible (unlike cpu instruction sets).

Basic object oriented concepts are needed already at this level, to be able to generate a whole self contained system. Ie what an object is, a class, a method etc. This minimal runtime is called parfait, and the same objects will be used at runtime and compile time.

Since working with at this low machine level (essentially assembler) is not easy to follow for everyone (me :-), an interpreter was created (by me:-). Later a graphical interface, a kind of visual debugger was added. Visualizing the control flow and being able to see values updated immediately helped tremendously in creating this layer. And the interpreter helps in testing, ie keeping it working in the face of developer change.

Target assembler

Risc is the last abstract layer, it is then translated into machine dependent code. This is not binary yet, more an oo version of assembler, where each instruction is represented by an object.

Arm is a risc architecture, but anyone who knows it will attest, with it’s own quirks. For example any instruction may be executed conditionally, ie every instruction carries bits to make it check the status register. Or the fact that there is no 32bit register load instruction. It is possible to create very dense code using all the arm special features, but this is not implemented yet.

The Arm::Translator translates RegisterInstructions to ArmInstructions.

Elf and Binary

A physical machine will run binaries containing instructions that the cpu understands, in a format the operating system understands (elf).

The previously generated objects must be able to convert themselves to binary. These binary codes are wrapped and stored into binary files of elf format. Arm and elf subdirectories hold the code for these layers. and the Elf::ObjectWriter creates Linux binaries.