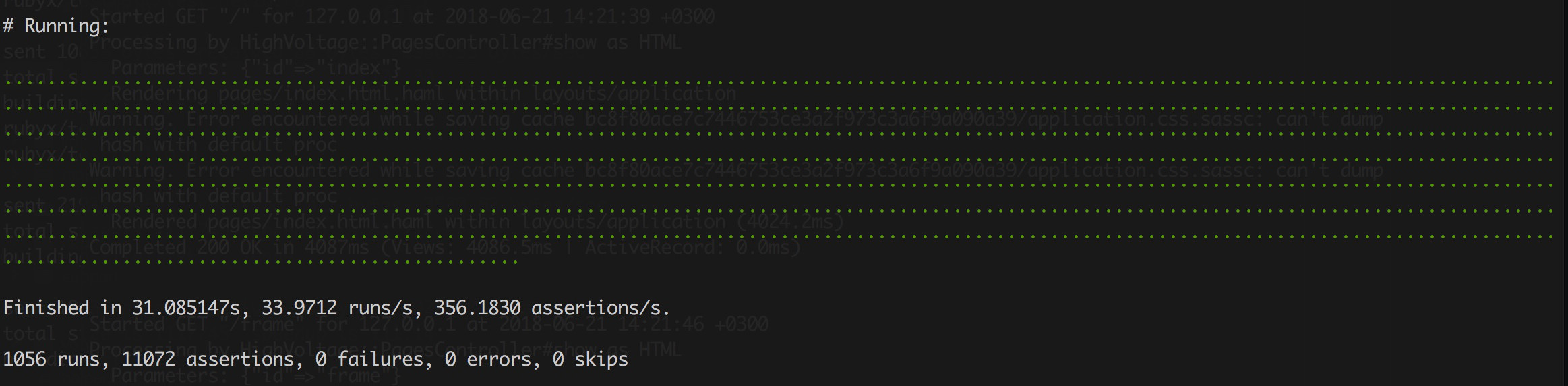

1000 tests and working binaries ( 2018-06-22 )

It was almost going to be working binaries and over 1000 tests. But i am coming more and more to the point where software is measured in number of tests, not lines of code.

1000+ Tests

It was shortly after the last post that i first noticed that 1k was approaching.

A little hard to grasp that i have written all those, kind of: what do they

all do?

It was shortly after the last post that i first noticed that 1k was approaching.

A little hard to grasp that i have written all those, kind of: what do they

all do?

A good step too: just about 200 tests in 2 months of work. I noticed the couple of times i didn't have good coverage for new code immediately, i started to have problems and had to write tests later. It seems it is the only way to understand even my own code anymore: by making the assumptions explicit. Some of the bugs where tests were missing are just the classics, +1 or -1 errors. And i feel a real newbie having to debug for 5 hours to find it was "<" not "<=" .

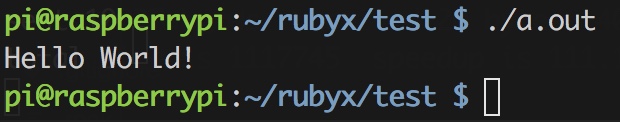

Working binaries

But off course it feels good to finally have

working binaries.

This is after all the first time that i compile real ruby into real binary.

The compiler does off course have many limitations, but what it does, it does

right. Even it was just Hello World for starters.

Off course i tried the next one straight after, "2+2" and .... it worked too.

I don't know if that is just my bad habit or an occupational thing, this

being surprised when things work.

Off course i tried the next one straight after, "2+2" and .... it worked too.

I don't know if that is just my bad habit or an occupational thing, this

being surprised when things work.

But a little bit about the journey and what how this works.

Positioning

Since ruby-x approach is oo from the start, we do not rely on the C way of creating binaries. Instead, the binary is a sort of snapshot of a running system, or in other words there is only heap.

This means we create binaries that look the same as the memory during runtime, which is made up of small fixed sized objects. Currently we only have objects of sizes 2 to the power of 2,3, 4 and 5. Maybe larger later, but with oo complete data hiding it is easy to extend objects transparently.

Constant loading

Especially for Code (the only objects larger than 16 words currently), this presented a challenge. Maybe even an extra challenge on top of the purely static one, because of the way ARM load constants.

Constant loading happens when a known object or address is loaded into a register. Arms constant 32bit instruction only allow 10 bit constants to be loaded. So if the constant is larger (eg the object further away) two instructions instead of one are needed. But this only becomes clear when all positions of objects have been determined.

Event approach

Off course this is not new, and this is in fact the third time i have coded this, finally getting it right. The problem gets hairy with the 16 words limit, when the code overlaps the originally assigned length and a new object has to be inserted.

To keep one methods code continuous, all other methods code has to be moved up, an thus a whole lot of positions change. Off course when some objects position change, a load depending on that may go from 1 to 2 instructions and so on and on. And then there are the branches that load their targets (forward and backward branches) off course, and they need to be updated etc etc.

I now have position objects which fire events, and about 4 different kind of listeners reacting in different ways when different objects change. The whole thing works, though as with many an event system, it is difficult to say exactly how. (only easy in the small, not the whole i mean)

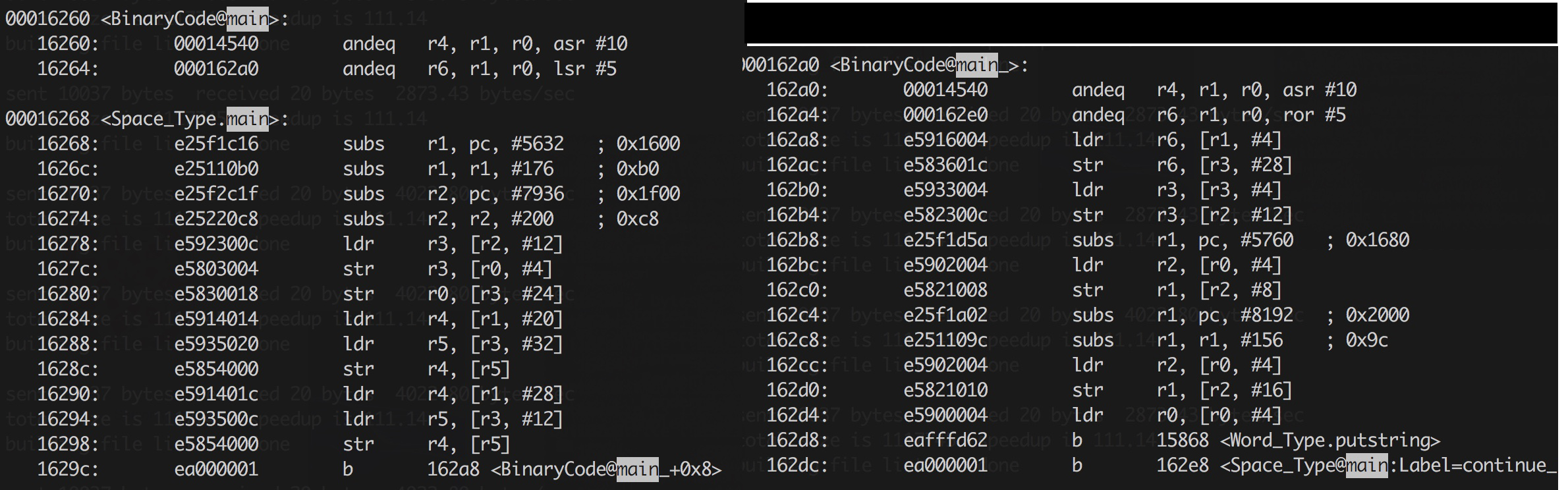

Object continuation

As i mentioned, it is quite straightforward to have larger data amounts, made up of 16 word chunks, by having a linked list. This is how the BinaryCode objects, that hold the binary code, do it.

But with the binaries there is an extra twist to this. The BinaryCode object has a header (the type and next), which are not code. So the code has to jump over this header at every end of an object.

This is demonstrated by the object dump above. If the assembly is scary, don't

worry, just look at the top left, address 16260, where the BinaryCode object for

the main method starts. You see the first two words are separated, as i said the

type and next (see the 162a0 value is the address of the BinaryCode on the right).

This is demonstrated by the object dump above. If the assembly is scary, don't

worry, just look at the top left, address 16260, where the BinaryCode object for

the main method starts. You see the first two words are separated, as i said the

type and next (see the 162a0 value is the address of the BinaryCode on the right).

Mainly i wanted to demonstrate the jump, which is the last instruction on the left side. The b stands for branch and the address 162a8 is exactly the code of the next BinaryCode, ie just after the header.

You can just make out on the bottom left, that this is in fact the code for the "Hello World" , as it jumps to the (Word_Type.) putstring.

Next steps

Hello World is off course a very small step and work will continue on making other things work. On the Interpreter side, many more things, like loops, conditionals, maths and dynamic dispatch already work.

Luckily, part of this push was to make the Interpreter a platform similar to the Arm. So it too has BinaryCode and works with addresses, not objects as before. In short the differences between Interpreter and Arm have shrunk, and there is good reason to believe that much will work quite soon.

Next i will build a testing framework to test the same code on Interpreter and Arm and see that both work. And specifically get all those working Interpreter tests working on Arm.

I think then it is time for some benchmarks. It has been a while since i made some, and they were quite promising. Especially loops of the Hello World and Fibonacci.

On the further horizon i was planning for continuations next, probably with a small rework of the return mechanism (unified return sequence).